The Governance of Prevention in italy

Morciano L,1 Caredda E1

1 Department of Biomedicine and Prevention; University of Rome “Tor Vergata”

Edited by: L. Palombi, E. De Vito, G. Damiani, W. Ricciardi

With a population of almost 61 million people, Italy is the sixth most populous country in Europe and the country with the second highest life expectancy.1-3 In fact, the percentage of people aged 65 or over represents 21.6% of the entire population, one of the highest levels in the world, while the fertility rate is low, at 1.3 per woman. Life expectancy reached 82.8 years in 2017, driven by reductions in mortality from cardiovascular diseases. However, a substantial gender gap persists, with life expectancy for women about five years higher than for men (85 vs 80.6 years life expectancy at birth). Disparities in life expectancy can also be observed between citizens with a higher educational level compared to Italians who have not completed their secondary education.2 Moreover, substantial differences exist among lifestyles, risk factors and health outcomes between the two halves of the country, with northern Italians showing a higher life expectancy, a lower mortality rate and a better health status in general. People living in the south often experience a worsening quality of life due to the presence of comorbidities, a higher rate of hospitalisation and a lower life expectancy.1,3

In Italy, the most detectable risk factors are represented by excess weight and obesity among children.2 Estimates confirm a high volume of disease due to behavioural risk factors, with dietary risks (11.2%), tobacco smoking (9.5%), high body mass index (6.1%), alcohol use (4.2%) and low physical activity (2.5%) contributing the most.4

The leading cause of mortality is still cardiovascular diseases and cancer, at a rate of more than two out of three deaths. Despite this, since 2000, dementia has been rising as a cause of mortality, representing 4% of all-cause mortality in 2014, and nervous diseases are the third absolute cause of death among Italian citizens.2

Health System Organisation

The Italian National Health System (INHS) was established on 23 December 1978, approved by an 85% vote in Parliament by means of Law No 833/78. The essential basis of the Italian NHS is represented by universal coverage, social financing from general taxation and non-discriminatory access to healthcare services.5 The system provides largely free healthcare at point of delivery.2 It is regionally based, with the central government sharing responsibility for healthcare with the regions.

The WHO and the OECD, along with various international entities, have considered the Italian NHS as having considerable strengths over the years. One of the most detectable instruments of healthcare planning is represented by the essential benefit package, the so-called Essential Level of Care (Livelli essenziali di assistenza, LEA), which must be provided on a uniform basis throughout the country.6,7

With the redistribution of competencies, the Government (i.e. the Ministry of Health) is now responsible for implementing central action to support regional prevention projects. In terms of prevention, the main policy and planning instrument in Italy is the National Prevention Plan (NPP).8 The NPP, via Regional Prevention Plans, represents a unique example of planning and implementation of prevention activities in Europe. It is delivered essentially every 3-5 years, with the current prevention plan being the NPP 2014-2018.9 The plan has a limited number of objectives common to the State and the regions, so as to allow regional planning to define the target population and the actions required to achieve the associated targets. The objectives of the current NPP are consistent with the macro-areas identified and are represented by:

- Reducing preventable and avoidable morbidity, mortality and disability from non-communicable diseases;

- Preventing the consequences of neurosensory disorders;

- Promoting mental health in children, adolescents and young people;

- Preventing substance addiction;

- Preventing traffic accidents and reducing the severity of their outcomes;

- Preventing home accidents;

- Preventing occupational accidents and diseases;

- Reducing potentially harmful environmental exposures;

- Reducing the frequencies of infectious diseases;

- Strengthening food and veterinary public health through safety prevention activities.

Once the main objectives are identified at national level, it is important to contextualise those targets in the regional epidemiological context. Moreover, to translate national guidelines into activities, it is necessary to adopt strategic actions focused on Evidence-Based Medicine and the concept of quality of care.

Another fundamental instrument of prevention policy and planning in Italy is represented by the National Plan of Vaccine Prevention (NPVP).10 The principle behind the vaccination plan is to standardise vaccination strategies over the whole country, in order to guarantee that the population has access to the full benefits of vaccination, intended as an instrument of both individual and collective prevention, regardless of residence, income and socio-cultural level. The Italian vaccination strategy is part of the European Vaccine Action Plan 2015-2020 and the Global Vaccine Action Plan 2011-2020 implemented the WHO.11,12 Because of the reduction in Italian vaccination coverage, on July 2017 the Ministry of Health enacted a law to increase the number of mandatory vaccinations from four to ten for minors up to 16-years-old.13

Delivery of Healthcare Services

The responsibility for healthcare in Italy is shared between the State and the 20 regions. The Ministry of Health is the principal entity responsible for public health at national level, with immunisation and screening programmes as priorities. Public health policies are implemented by the regions. At local level, responsibility for the delivery of services falls to the Local Health Authorities (ASL). These entities provide primary care – including family medicine and community services – and secondary care, mainly through the department of prevention, preventive medicine and public health services. The territory of each ASL is further divided into districts, and these represent the institutional level that directly controls the provision of public health and primary care services.1-4

The immunisation programme

Vaccinations are considered a priority for Italian public health policy. With Law No 119 of 31 July 2017, ten vaccinations became mandatory throughout the country, for all Italian and foreign children until the age of 16 years.13 Moreover, being vaccinated permits access to kindergarten and failure to comply with the vaccination schedule can result in penalties. Before this law was introduced, there were four mandatory vaccinations: diphtheria, tetanus, poliovirus (oral poliovirus vaccine – OPV) and the Hepatitis B vaccine, which was introduced in 1991 for all children and newborns up to 12 years of age. With the introduction of the law, mandatory vaccinations for all children and newborns, both Italian and foreign, up to 16 years of age, also cover pertussis, measles, mumps, rubella, Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) and chickenpox. Vaccinations against HPV, meningococcal B, meningococcal C, pneumococcal meningitis and rotavirus are strongly recommended.

National screening programme

Since 2001, secondary cancer prevention has been included in the LEA package. Screening programmes are organised at local level by the ASL and screening invitations are provided for the target population.14

Screening for cervical cancer is free for all women from 25 to 64 years of age every three years, in accordance with European guidelines.15

Mammography screening for breast cancer is offered every two years to all women from 50 to 69 years of age.16

Colorectal cancer screening is offered to male and female individuals from 50 to 74 years of age, in two ways: most regions carry out faecal occult blood tests, while others provide flexible sigmoidoscopy.17 Thanks to the screening programmes, significant progress has been made in recent years in reducing mortality and disease burden for cervical cancer, breast cancer and colorectal cancer.

Financing

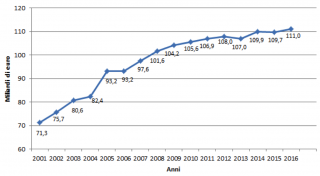

The National Health Service is largely funded through national and regional taxes, supplemented by co-payments for pharmaceuticals and outpatient care. Within Italy, there are substantial differences in funding between regions, with per capita expenditure ranging from 10.2% below the national average to 17.7% above.18,19 The National Health Fund allocation has grown since 2000, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. National health fund in billions.

Regions are required to distribute their resources more or less along the following lines: primary care (44%), secondary-tertiary care (51%) and prevention (5%). To date, the total expenditure for prevention is under the percentage of 4.5% (almost 4.2% of the total funding is used for prevention). The largest share of expenditure on prevention was in the area of hygiene and public health (44.5%), followed by veterinary public health (23.8%), occupational hygiene (13.3%) and food hygiene (7.9%). Other costs accounted for approximately 10% of expenditure on prevention.20,21

Workforce

The workforce tasked with public health activities is engaged in many sectors, and it is difficult to estimate its size. An analysis of the distribution of the public health workforce across different regions is not available. Estimates can be produced on the basis of the number of workers in the Department of Prevention and of the members of the Italian Society of Hygiene, Preventive Medicine and Public Health: in 2015, the average number of members was around 4.6 per 100,000 population. In Departments of Prevention, the average staff is around 182 members, which corresponds to one worker for every 2,300 citizens.

To date, no exact data are available about the number of workers employed in the public health sector.21

Conclusion and Outlook

Italian prevention services are largely public and free at point of delivery. Immunisation and screening programmes represent priorities in the public health area, although with differences in services between regions. Some of the main efforts to be made in the next few years will relate to prevention of inequalities, filling the gap between the two halves of the country and standardising the health status of the population.18,19,22,23 In fact, to date, there is a clear gap between the north and south of the country.1-3 Life expectancy in southern regions is 2.9 years below that in the north, and obesity and other behavioural risk factors generate worse outcomes for citizens in the south of the country.24 Moreover, compliance with screening programmes is lower in the south, with consequently worse outcomes in terms of cancer therapies and survival.25 Another critical point is represented by the low funding and expenditure on public health programmes. Although the fixed percentage of expenditure is 5%, the Italian Government has never been exceeded 4.2% of public health funds.4 Despite this, Italian prevention services seem able to guarantee a high standard of quality of care, which is remarkable in terms of high life expectancy at birth, and two-thirds of Italians claim to have a good health status.26 In fact, international agencies, such as the WHO and the OECD, have ranked Italy’s NHS as one of the best in the world.3

References

- Ferré F, et al. Italy: Health System Review. Health Systems in Transition, 2014, 16 (4): 1-168.

- OECD. State of the Health in the EU. Italy: Country Health Profile 2017. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/355985/Health-Profile-Italy-Eng.pdf?ua=1.

- Malizia A, et al. (2017) Emergency Department, Sustainability, and eHealth: A Proposal to Merge These Elements Improving the Sanitary System. The Internet of Things: Foundation for Smart Cities, eHealth and Ubiquitous Computing, Chapter 17, CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group.

- France G, Taroni F, Donatini A. The Italian Healthcare System. Health Econ. 2005; 14: 187-202.

- Ministry of Health. http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/salute/p1_4.jsp?lingua=italiano&area=Il_Ssn.

- Ministry of Health. Cosa sono i LEA [What are the LEA]. http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/temi/p2_6.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=1300&area=programmazioneSanitariaLea&menu=lea.

- Monitoring Table LEA 2016. http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/documentazione/p6_2_2_1.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=2783.

- Ministry of Health. National Prevention Plan. http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/temi/p2_4.jsp?lingua=italiano&tema=Prevenzione&area=prevenzione.

- Ministry of Health. National Prevention Plan 2014-2018. http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2285_allegato.pdf.

- Ministry of Health. National Plan for Vaccination Prevention 2017-2019. http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/vaccinazioni/dettaglioContenutiVaccinazioni.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=4828&area=vaccinazioni&menu=vuoto.

- WHO. European Vaccine Action Plan 2015-2020. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/vaccines-and-immunization/publications/2014/european-vaccine-action-plan-20152020-2014.

- WHO. Global Vaccine Action Plan 2011-2020. https://www.who.int/immunization/global_vaccine_action_plan/GVAP_doc_2011_2020/en/.

- Law No 119 of 31 July 2017. http://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2017/08/05/182/sg/pdf.

- Ministry of Health. Screening. http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/salute/p1_4.jsp?area=Screening.

- Ministry of Health. Screening for Cervical Cancer. http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/salute/p1_5.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=27&area=Screening.

- Ministry of Health. Screening for Breast Cancer. http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/salute/p1_5.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=23&area=Screening.

- Ministry of Health. Screening for Colorectal Cancer. http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/salute/p1_5.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=24&area=Screening.

- Serapioni M. Economic Crisis and Inequalities in Health Systems in the Countries of Southern Europe. Cad. Saude Publica 2017; 33 (9).

- Dyakova M, Hamelmann C, Bellis MA, et al. Investment for Health and Well-Being: A Review of the Social Return on Investment from Public Health Policies to Support Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals by Building on Health 2020. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2017 (Health Evidence Network (HEN) synthesis report 51).

- Hamelmann C, Turatto F, Then V, Dyakova M. Social Return on Investment: Accounting for Value in the Context of Implementing Health 2020 and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2017 (Investment for Health and Development Discussion Paper).

- Poscia A, Silenzi A, Ricciardi W. Organisation and Financing of Public Health Services in Europe. Health Policy Series 2018: 49.

- Rosso A, Marzuillo C, Massimi A, et al. Policy and Planning of Prevention in Italy: Results from an Appraisal of Prevention Plan Developed by Regions for the Period 2010-2012. Health Pol 2015; 119: 760-9.

- WHO. Nutrition, Physical Activity and Obesity. Italy. 2013. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/243306/Italy-WHO-Country-Profile.pdf.

- Unim B, De Vito C, Massimi A, et al. The Need to Improve Implementation and Use of Lifestyle Surveillance System for Planning Prevention Activities: An Analysis of the Italian Regions. Publ. Health 2016; 130: 51-8.

- WHO. European Health Report. More than Number – Evidence for all 2020. http://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/european-health-report-2018.-more-than-numbers-evidence-for-all-2018.

- Boccia A, De Vito C, Marzuillo C, Ricciardi W, Villari P. The Governance of Prevention in Italy. EBPH 2013; 13 (1).